|

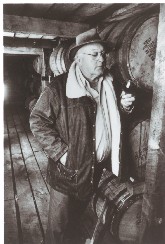

Booker Noe, sixth generation, unfiltered and uncut

By F. Paul Pacult

The following is an excerpt from American Still Life: The Jim Beam Story and the Making of the World’s #1 Bourbon by F. Paul Pacult (John Wiley & Sons, $24.95) available wherever books are sold.

Spending time in Bardstown with Jim Beam’s grandson Booker Noe and his family is akin to time-warping back to a magical era when America was painted in sepia-tinted pictures. Corny as it sounds, those images are of general stores with wood-plank floors, fireflies trapped in mason jars, wooden school desks with ink wells, men and women all wearing hats and of barefoot boys ambling down a vacant dirt road to the local fishing pond on a late June afternoon, dragonflies hovering above it. My wife and I entered the big, sturdy brick home on North Third Street, the old home of Jim Beam to the intoxicating aroma of not bourbon whiskey but of ham and homemade biscuit sandwiches. An unseen clock chimed the hour, welcoming us. Spending time in Bardstown with Jim Beam’s grandson Booker Noe and his family is akin to time-warping back to a magical era when America was painted in sepia-tinted pictures. Corny as it sounds, those images are of general stores with wood-plank floors, fireflies trapped in mason jars, wooden school desks with ink wells, men and women all wearing hats and of barefoot boys ambling down a vacant dirt road to the local fishing pond on a late June afternoon, dragonflies hovering above it. My wife and I entered the big, sturdy brick home on North Third Street, the old home of Jim Beam to the intoxicating aroma of not bourbon whiskey but of ham and homemade biscuit sandwiches. An unseen clock chimed the hour, welcoming us.

The present-day Noes of Bardstown, Booker, Annis and their son Fred and his family, are the link, the flesh-and-blood lifeline to the generations of Beams who have since 1795 made straight bourbon whiskey as well or better than anyone else in Kentucky. Booker retired in the early 1990s, becoming master distiller emeritus and official Beam spokesman for the bourbon whiskeys. Until recently, he could still be found walking around the aging warehouses sniffing the maturing bourbon whiskeys to gauge solely by his acute olfactory sense which ones will be extra special.

“Aw hell, I remember it like it was yesterday,” bellowed Booker, all 6 foot, 4 inches and 360 pounds of him on a light day as we camped in his and Annis’s sitting room in Bardstown, the same room that his grandfather Jim Beam used to sit, entertain and silently observe all who were present. Born in 1929 to Margaret Beam Noe, Jim Beam’s daughter, and Frederick Booker Noe, Frederick Booker Noe II had left big impressions his whole life. Why stop now?

“My first recollection of bourbon is when my grandfather took me to the distillery at Clermont...must have been 1938, maybe 1939, I was about ten years old, I guess. I recall going up stairs, the steps up to look down into the fermenting vats…wooden tanks back then whereas today they’re all stainless steel.”

Booker paused as he pondered.

“I remember the smell. I remember sniffing the grain smell. Grandfather showed me the fermentation. It was belching gas and moving. Like it was alive. The motion of it was rolling from one side to the other, belching gas, and I recall thinking it was going to spill over the sides.” Booker laughed at the completely reasonable conclusion of a young boy, his first time seeing, smelling, hearing the family distillery.

While audio tapes commissioned by the Kentucky Historical Society of Bardstown of Jim Beam’s contemporaries described Prohibition, Jim Beam and what he was like, Booker remembers his legendary grandfather in the fondest of terms but in a different way. After all, this was the man who along with Booker’s uncle T. Jeremiah Beam selected him to carry the family mantle. While some written accounts had painted Jim Beam as being something of an extrovert and bon vivant, Booker narrated a different story, described a different man than otherwise characterized.

“Grandfather was a quiet type of person. He wasn’t a blowhard. We’d come here to this house for the holidays. He always wore a shirt and tie around the house. Liked a diamond stickpin in his tie. He would sit quietly. He did a lot of observing. Some relatives, like George Beam, grandfather’s nephew, and his wife, thought he was a stuffed shirt. But then, hell, they were missionaries in Greece,” recalled Booker, nodding his head.

Booker moved into the big house with his grandmother after his grandfather’s death in 1947. Booker was eighteen. “I do remember my grandmother saying ‘Jim almost runs us out of the house with that yeast.’ Of course, grandfather made the yeast culture right here in the kitchen and it would smell, well, hell, kind of sulphury…almost, can I say it, like a privy.” He whispered privy, making sure that Annis and Toogie wouldn’t hear the coarse word.

Booker related that his uncle Jere gave him the family yeast culture formula prior to his death in 1977. Booker, in the role of master distiller, created the culture in the North Third Street house for years. Cautious like his grandfather, Booker said, “I kept it here in the deep-freeze ‘cause you never know.”

So, if Jim Beam was in truth a “quiet type”, what about Booker’s uncle T. Jeremiah Beam, the fifth generation? “Ohhh-ohhh,” said Booker, shaking his head side-to-side, “He was more of a party guy than grandfather. Jeremiah was what known as a ‘ball man’. He loved every type of ball game there was. Old Carl Beam used to tell a joke. Carl would ask ‘Where’s Jere Beam?’ Then he’d answer, ‘Find the biggest ball game in the country and that’s where Jere Beam is.’”

“That’s an exaggeration, though, isn’t it?”

“Exaggeration?” boomed Booker. “Hell, when grandfather died on December 27, 1947, Jere was on his way to the Sugar Bowl. Hell, the state police had to stop him, pull him over on the side of the road to tell him his father’d died.”

Prohibition ended in 1933 when Booker was four years old. But he does remember the stories told to him by his uncle and cousins about the wild and difficult years of shutdown. “There were seventy-five to one hundred distilleries within a 25-mile radius of Bardstown before Prohibition. They all closed. Only a few reopened after repeal. Grandfather wanted to get his son into the business so that he could pass the tradition of whiskey making on. It took a lot of effort at the age of seventy to start over. Jere had done a lot of partying at school and hadn’t gotten to know the distilling business, so he started from scratch.”

During Prohibition, Booker retold stories he had heard from Earl, his cousin, of how big, black cars with Illinois license plates would be seen driving at night through Bardstown, hauling away the stockpiled whiskey and taking it back to Chicago. There was money to be made in bootleg whiskey, after all. “Ol’ Al Capone liked bourbon whiskey, I heard, ‘til it ran out” cracked Booker. When the whiskey stocks were finally depleted, the big black cars with Illinois plates ceased making their nocturnal visits to north-central Kentucky.

Booker started working for James B. Beam Distilling Company in 1950 at the age of twenty-one. “I just went to work. Hands on. There were no classes. I learned how to do everything all at once. Worked in the yeast room. Managed the boilers that generated the steam for the stills.”

Who were his tutors, his biggest influences in the science and art of bourbon whiskey distilling?

“Well, there was my uncle Jere and Carl, his cousin, and Park Beam. I just went right into the manufacturing part of the business. Learned something from each of them.”

During his apprenticeship Booker remained at the Clermont plant for more than three years. Then when the second plant at nearby Boston became operational in 1954, he was named distiller there. Booker stayed at Boston making bourbon whiskey for the better part of forty years. “In 1950 at Clermont, we converted 8,000 bushels of grain a week to 40,000 gallons of spirit. That was per week,” said Booker.

The common conversion ratio for bushels of grain to fresh distillate is one-to-five, meaning for every bushel of grain fermented and distilled the modern Kentucky bourbon distiller gets five gallons of raw spirit. That harsh spirit will become bourbon whiskey following the legal minimum of two years in charred oak barrels. Distillers from the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century had a conversion ratio more in the neighborhood of a one-to-two and a half or, on good days when all the equipment was properly working, one-to-three. Drawing the comparison over a half-century, Booker said, “Today when both plants are working full-out, we produce 90,000 gallons of spirit in a day.”

Through the 1950s the number one selling straight bourbon whiskey was Old Crow Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey. “Old Crow and Jim Beam were like this (Booker brandished two massive digits stuck together to illustrate his point). Then, in the late 1950s, maybe 1960 Jim Beam pulled ahead and that’s been it ever since.” Today, Jim Beam Brands Worldwide owns the Old Crow brand.

Booker was named master distiller of the James B. Beam Distilling Company in 1960. During Booker’s stellar four decades long tenure as master distiller he upped production to meet the demand a dozen times. Under his guidance, Jim Beam Bourbon achieved true international status and well-deserved fame as a world-class brand. Asked to sum up his five decades of being intimately involved with the bourbon whiskey industry, the family business, Jim Beam Bourbon and the creator of Booker’s Bourbon, Booker in the tradition of his grandfather modestly replied, “It’s been a good ride. Hell, been a good ride.”

F. Booker Noe II wouldn’t ever acknowledge it, much less say it, but his grandfather and uncle could not have chosen a more worthy successor, one who could have better embodied the pure essence of whiskey-making in Kentucky.

|